How Geometry is Fundamental for Chess

The development of geometry in humansUnderstanding Geometrical Concepts

Humans are the only animals that we know that understand geometrical concepts.

Humans are the only animals that we know that understand geometrical concepts. Things like lines and shapes (triangles, squares, circles etc.). Not only do we understand these concepts, we can also combine them in a infinite, recursive way to form new geometrical forms. We can also transform them through rotation. This is important for chess. Chess relies on geometrical concepts fundamentally. The concept of a line of varying discrete lengths (a line distance of 1 for a pawn, 2 on the first move). A vertical line rotated by 45 degrees for the length of a bishop. A knight is an example of a recursive transformation, combining 1 and 2 length lines at 90 degree angles. Same with the queen (diagonal and straight). Numerosity is also fundamental. The piece involves an understanding of numerosity to move a certain amount of squares.

This may seem obvious, but it needs to pointed out because everyday experience disguises the miracle. These geometrical concepts do not exist in nature. There are no lines and squares. If it's obvious then why did it take 4.5 billion years since the development of life to emerge?

Animals do not possess a sense of discrete numbers.

Animals don't possess a sense of discrete numbers. Chimpanzees, instead of seeing 6 and 7, they feel 6ish-7ish. This is shown when they have to pick a plate with the most food. The further the difference between the amount of chocolate chips, the easier it is for them (e.g. choosing between 2 and 10 chocolate chips). They get it right when it's between 1 and 2 chocolate chips. But if it's between 6 and 7, then it's difficult, the performance decreases when the ratio between the amount of chips decreases. This is represented by Weber's Law which states that the threshold needed to detect a stimulus grows in proportion with the initial stimulus (e.g. to have an equal performance for comparing 1 vs 2 chips might have to have an equivalent of 6 vs 12 chips as an example). Without a sense of discrete numbers, you can't play chess.

There was a study where they had bonobos try to pick out the odd shape out.

Image 1. Find the shape that is not a regular square. Image 2. Find the shape that is a regular square. This is easy for you but not for bonobos. They can only get a 50% success rate even after extensive training. Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024) Two brain systems for the perception of geometric shapes.

Image 1. Find the shape that is not a regular square. Image 2. Find the shape that is a regular square. This is easy for you but not for bonobos. They can only get a 50% success rate even after extensive training. Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024) Two brain systems for the perception of geometric shapes.

Humans and bonobos had tasks like this where they had to spot the odd shape out. Bonobos were trained to pick out the odd shape, through being rewarded. On the left you can see that the odd shape out is the diamond on the bottom left, it's not a square like the others. The inverse scenario is shown on the left. It's easy for humans to spot the odd shape out, but bonobos struggle, only getting a 50% rate for identifying it. Furthermore there success rate was equally poor no matter whether they were trying to find the odd shape out in this easy example, vs having to find the odd shape out where the shapes were more complicated (shown below). This means only humans have the ability to understand geometric shapes.

Where squares were involved or not as an odd object out, baboons made the same amount of errors (75% of first trials improving to 50% on later trials, but this patterns was the same not matter where the shape to be detected was a regular square or a not a regular geometric shape). Humans only made 0-10% errors on the simpler shapes, increasing to 40% on shapes that had no symmetry. Dehaene et al. (2022) Symbols and mental programs: a hypothesis about human singularity.

Where squares were involved or not as an odd object out, baboons made the same amount of errors (75% of first trials improving to 50% on later trials, but this patterns was the same not matter where the shape to be detected was a regular square or a not a regular geometric shape). Humans only made 0-10% errors on the simpler shapes, increasing to 40% on shapes that had no symmetry. Dehaene et al. (2022) Symbols and mental programs: a hypothesis about human singularity.

Understanding regular shapes means we can create a 8x8 chess board through squares. This involves the concept symmetry/repetition.

Shapes are hypothesized to be formed by a programming language in the brain.

"In various cultures and at all spatial scales, humans produce a rich complexity of geometric shapes such as lines, circles or spirals. Here, we propose that humans possess a language of thought for geometric shapes that can produce line drawings as recursive combinations of a minimal set of geometric primitives. We present a programming language, similar to Logo, that combines discrete numbers and continuous integration to form higher-level structures based on repetition, concatenation and embedding, and we show that the simplest programs in this language generate the fundamental geometric shapes observed in human cultures. On the perceptual side, we propose that shape perception in humans involves searching for the shortest program that correctly draws the image (program induction). A consequence of this framework is that the mental difficulty of remembering a shape should depend on its minimum description length (MDL) in the proposed language. In two experiments, we show that encoding and processing of geometric shapes is well predicted by MDL. Furthermore, our hypotheses predict additive laws for the psychological complexity of repeated, concatenated or embedded shapes, which we confirm experimentally."

Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024). A language of thought for the mental representation of geometrical shapes

Shapes are hypothesized to be formed by a programming language in the brain. This programming language can generate more complicated shapes by combining numerosity, rotation and symmetry around a axis, and repetition. Minimum description length (MDL) is the minimum length you need to describe something. If shape A has a lower MDL than Shape B, then it should be easier to remember because the description has a shorter length. It's easier to remember a zigzag pattern vs a completely random pattern. The zigzag pattern can encoded in a program which can reproduce geometrical patterns, and combine them with each other, allowing it's MDL to be lower than the random pattern which can't be described effectively by geometric principles/patterns (repetition, symmetry etc.).

The human brain invented shapes and imposed it on visual processing, not the other way around.

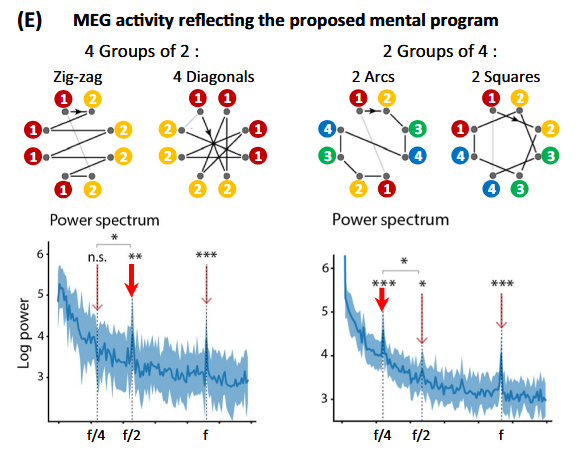

The patterns are converted to geometrical regularities with the use of symmetry and repetition. Brain activity supports this view as measured using Magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures magnetic fields causes by electrical activity in the brain. Macaque monkeys can't reproduce the pattern's shown above, it took thousands of trials to be able to get them to represent only 4 locations. Monkey's only saw the ordinal pattern of these dots. A dot pattern representing going along a circle vs a completely random dot pattern would be all the same to a monkey, but a human would notice the difference immediately. Dehaene et al. (2022) Symbols and mental programs: a hypothesis about human singularity

The patterns are converted to geometrical regularities with the use of symmetry and repetition. Brain activity supports this view as measured using Magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures magnetic fields causes by electrical activity in the brain. Macaque monkeys can't reproduce the pattern's shown above, it took thousands of trials to be able to get them to represent only 4 locations. Monkey's only saw the ordinal pattern of these dots. A dot pattern representing going along a circle vs a completely random dot pattern would be all the same to a monkey, but a human would notice the difference immediately. Dehaene et al. (2022) Symbols and mental programs: a hypothesis about human singularity

"From these observations, one is left wondering what could be the origins and evolutionary advantage of the human competence for abstract geometry. We propose that it is a specific case, in the visual domain, of a general human ability to decompose complex percepts and ideas into composable, reusable parts – an ability which led to a massive enhancement of human productions, from architecture to tool building, and of the capacity to understand the abstract features of the environment."

Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024). A language of thought for the mental representation of geometrical shapes

Minimum Length Description explains the paradox of why circles are viewed as a simple shape. Technically circles are the most complicated as they have infinite sides. But circles are easier to conceptualize then a 17-sided polygon for example, even though a circle has infinite sides. The Minimum Length Description gives an answer to this. The answer is that a circle only needs one angle rate parameter: a circle is formed by a single line with a constant rate of rotation from one of its endpoints. Now the description switches from amount of sides to a single angle sweep rate parameter.

Being able to represent complex geometrical sequences allows us to create the movements which guide the chess pieces. It also allows us to memorize opening theory and chess games. If you think about it, thinking about chess moves is incredibly complicated, involving memorizing or visualizing long sequences of geometrical patterns. You don't notice this because it feels normal and the piece visuals make it seem like the moves emanate from them naturally.

Everyday experience disguises the miracle.

Sources

Stanislas Dehaene (1997). The Number Sense

Dehaene et al. (2022). Symbols and mental programs: a hypothesis about human singularity

Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024). A language of thought for the mental representation of geometrical shapes

Sablé‐Meyer et al. (2024). Two brain systems for the perception of geometric shapes

---

Visit Blog Creators Hangout for more featured blogs.

You may also like

Kevin_M06

Kevin_M06Deep Analysis of Lichess Puzzles

Ahh... Lichess puzzles. Don't we love them? RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000The Brain Science of Chess

How does the brain play chess? CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000Karpov vs Kasparov: The Rivalry (Part 1: 1975-1985)

Explore One of the Greatest Rivalries in the History of Chess RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000All about the Elo Rating System

Explore the Elo Rating System which determines your FIDE Rating ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_Stats